Prior to the global financial crisis, many central banks were a misunderstood relic of the economic system. Since the crisis began, however, central banks became an integral part of the day-to-day functioning of the financial markets, and more broadly the economy. As we move past the financial crisis, central banks are in the unsavory role of unwinding support mechanisms while avoiding the throes of a new crisis.

By most measures, the recession is over. That is true in many respects, but the effects of the financial crisis are still being seen in numerous pockets around the globe, be it housing, labor markets or the European debt crisis. In order to combat the lingering hangover from our multi-decade credit binge, central banks, specifically the Bank of England (BoE), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve, actively sought to resuscitate the economy from its doldrums and to their credit, those efforts appear to have worked.

Emerging markets, on other hand, were largely unscathed during the crisis. Yes, there was a notable slowdown in growth, but the time to recovery was relatively short, and emerging market nations are already back on stable ground, with one caveat – inflation.

So, now what?

Central banks in the developed world are not yet ready to signal the all clear and begin tiptoeing away from the markets. There are indications that the exit is moving closer, but thus far, there are no definitive changes in policy. Following its early March policy meeting, for instance, ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet said that “an increase in interest rates at the next meeting (April 7th) is possible.”

According to the markets, though, at least one rate hike in the EU is a foregone conclusion, but US hikes are not likely to happen any time soon. In fact, there is less than an 8% chance that overnight interest rates will change by early August and a 26.0% chance of a rate hike by December. Those percentages are actually trending lower since the start of the year as traders grapple with a sluggish recovery and the realization that the Fed is in no hurry to change its stance.

The BoE is in a tighter bind than the US at the moment. Inflation in England currently stands at 4.4% over the past year, more than double the target 2.0% rate. At the March 9th and 10th monetary policy meeting, three committee members out of nine voted against holding rates at 0.5%. One committee member went as far as indicating that a 50 basis point (one basis point = 1/100th of 1%) rate increase was warranted.

Loose monetary policy in the developed world is making the situation in emerging markets more complicated by the day. Of the 21 countries in the MSCI Emerging Market index, the overwhelming majority are in the process of tightening monetary policy.

China, for example, is attempting to cool its economy by soaking up excess liquidity from its banking system. For the third time this year, the People’s Bank of China increased the bank reserve requirement ratio by 50 basis points to 20.0%. For every dollar deposited in Chinese banks, 20.0% is now required to be set aside at China’s central bank.

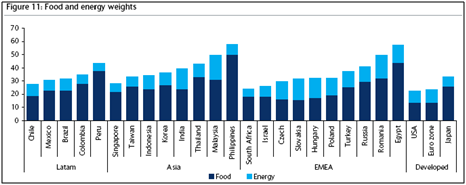

The difficulty in managing monetary policy for emerging market central banks is that food and energy costs represent a far greater outlay in those economies.

In countries such as the Philippines, food and energy is a more than 50.0% weight in its inflation index. For the largest emerging market economies, Brazil and Korea, in particular, food and energy is roughly 30% of inflation. By comparison, food and energy accounts for less than a 20.0% weight in the US consumer price index.

As pressure builds around the globe, it is important to remember the Federal Reserve’s mandate: “maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.” With domestic labor markets stagnating and consumer prices largely stable, there is no reason to suspect a suddenly aggressive policy mantra will be in the Fed’s future. This will inevitably spill over into the emerging markets and create the possibility of new asset bubbles. Central bankers in those emerging market economies are well aware of what is occurring.

The global economy is more closely interwoven than at any time in history. Managing rampant inflation and excess liquidity becomes increasingly difficult for emerging market central banks when their developed equivalents are hesitant to turn off the spigots. Without a clear policy directive from developed nations, emerging market countries will likely be caught in a tumultuous cycle of inflation and asset bubbles.

The Lighter Side